Nvidia GeForce RTX 4000 series graphics cards: promising specs but major pricing problems

6 min read

The Nvidia GeForce RTX 4000 series graphics cards have arrived in all their glory. Built on the “Ada Lovelace” microarchitecture and TSMC’s cutting-edge 4 nm transistors, the RTX 4000 series promises two to four times the performance uplift over similar cards from the previous generation. They also bring the vastly improved Deep Learning Super Sampling (DLSS) 3.0, and a new Shader Execution Recording (SER) engine that’s supposed to help its revamped ray tracing cores run more efficiently.

However, the series’ prowess is diminished by a confusing price structure and high costs, leaving the gamers who have held off from upgrading through the pandemic to wonder why.

At the top of the launch stack is the RTX 4090. Carrying 16,384 CUDA graphics cores and 24GB of GDDR6 memory, the card is meant to run games at quality settings in 4K resolution. Its price reflects its prestige, coming at an eye-watering US$1,599.

While its asking price may knock the enthusiasm out of some buyers, it’s not entirely unreasonable to add US$100 to the MSRP of the previous best enthusiast card, representing a six per cent increase, especially considering that the RTX 4090 sports a new architecture, is built on a bleeding-edge node, and features improved ray tracing cores. What is confusing, however, is the way Nvidia positioned its RTX 4080s.

Traditionally, Nvidia would release a single product for every performance tier upon launch. Each tier had distinct hardware differences appropriate to its cost. The company would add finer segmentation with Ti and Super variants as time passes.

In this generation, however, Nvidia split the high-end tier, previously occupied by a single xx80 card, into two variants right off the bat, one with 16GB of memory, and another with 12GB of memory.

| Name | GeForce RTX 4090 | GeForce RTX 4080 (16GB) | GeForce RTX 4080 (12GB) |

| NVIDIA CUDA Cores | 16,384 | 9,728 | 7,680 |

| Boost Clock | 2.52 GHz | 2.51 GHz | 2.61 GHz |

| Memory Size | 24 GB | 16 GB | 12 GB |

| Price | US$1,599 | US$1,199 | US$899 |

Like many others who saw Nvidia’s launch presentation, I can’t help but think that the 12GB variant is what the RTX 4070 should be. In addition to the lower memory capacity, the RTX 4080 12GB variant also has a significantly downgraded GPU, having just 7,680 CUDA cores versus the 9,728 on the 16GB version, amounting to a 20 per cent reduction in core count. Furthermore, the 12GB variant also has a much narrower 192-bit memory bus, compared to the 256-bit on the 16GB variant. We’ll have to wait for independent reviews to show if the cutdown equates to a 20 per cent performance difference and if the narrower memory bus actually chokes performance.

And these cards are expensive with a capital E. The RTX 4080 12GB is 29 per cent more expensive than the launch price of the RTX 3080 10GB (US$899 vs US$699), and the RTX 4080 16GB is a whopping 72 per cent more expensive (US$1,199 vs US$699).

This sharp climb brings affordability into question. Regardless of the cards’ performance, consumers experiencing stagnant wages amid inflation may find them to be unattainable. In August, the U.S. inflation rate remained at 8.3 per cent. And although average personal income has been increasing for six consecutive months, it’s nowhere near enough to keep pace.

U.S. Personal income increases by month. Source: tradingeconomics.com

Nvidia’s decision to split the RTX 4080 is reminiscent of what happened at the height of the cryptocurrency boom and the semiconductor shortage. Last year, gamers felt the sticker shock when graphics prices were exorbitantly inflated due to short supply. It was then Nvidia announced the RTX 3080 12GB variant, coming with 2GB of extra memory over the original and 256 more CUDA cores, for US$100 more. These improvements only yielded marginal performance increases and were widely seen as underwhelming relative to the increase in cost. How Nvidia positioned the RTX 4080s is arguably far worse.

Speculations as to why Nvidia chose to do this spread immediately. The prevailing theory appears to be that Nvidia is using the price pressure to sell its leftover RTX 3000 series graphics cards. A quieter theory is that supply chain constraints combined with sky-high inflation have forced Nvidia to raise the price to actually generate a profit.

Whatever Nvidia’s logic is, this decision will cause problems. The launch of the RTX 4000 series was wedged between an awkward trifecta of the Ethereum merge, losing a key partner, and competition from AMD. Let’s walk through each of these factors.

The Ethereum Merge

Ethereum is one of the most popular cryptocurrencies, second only to Bitcoin. On Sept. 15, the cryptocurrency went through The Merge, a transition that saw the Ethereum Mainnet merging with another blockchain called Beacon chain. As a part of the transition, Ethereum switched from a proof-of-work model to a proof-of-stake model, reducing its energy consumption by 99.95 per cent. This was possible because the merged chain no longer generates blocks through mining.

This is significant in two ways. One, there will be drastically fewer miners who hoard pallets of graphics cards; and two, the used graphics card market will see an influx of inventory.

On the former point, it’s hard to believe that Nvidia, a multi-billion dollar company that enjoyed a meteoric rise during the pandemic, could misjudge demand for such a critical launch. The company’s either confident that its product will dominate the market, or knows that it will sell.

The latter is already in full swing; listings for used RTX 3000 cards have flooded sites like eBay and Kijiji (whether gamers will want to buy a used mining card is another story).

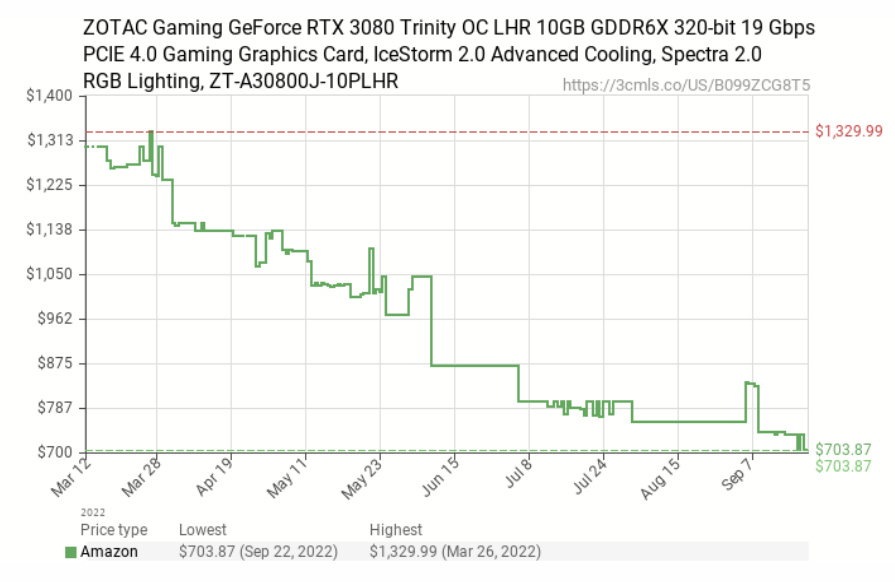

Almost in tandem, prices of the RTX 3000 series graphics cards on retailers like Amazon have fallen across the board to near-MSRP levels.

According to Steam’s August 2022 hardware survey, the most popular graphics card is still the Nvidia GeForce GTX 1060, which is now over seven years old. The RTX 3000 series doesn’t make an entry until fifth place. For those holding out to upgrade, picking up an RTX 3000 series card at a discount could still yield tremendous performance improvements. The RTX 3070, which can now be purchased for around US$500 on Amazon, is more than twice as fast as the GTX 1060, and offers a plethora of newer features like DLSS and ray tracing.

EVGA and the partner ecosystem

On Sept. 16, Gamers Nexus and JayZTwoCents dropped a bombshell when they reported that EVGA, one of Nvidia’s biggest board partners, had announced its exit from the graphics business, citing disrespectful treatment from Nvidia as the key reason.

In an interview with Steve Burke, managing editor of Gamers Nexus, EVGA chief executive officer Andrew Han explained that the decision is not a financial one. He listed several problems, like Nvidia not releasing the MSRP or the supplier cost to board partners until the product announcement, and cutting into the sales of partnered products with Nvidia’s first-party Founder’s Edition cards at lower prices.

Regardless of the root cause, graphics card sales accounted for 80 per cent of EVGA’s revenue, so cutting it definitely wasn’t an easy call. Without it, EVGA will have to rely on its power supplies, motherboards, and other products, which are much smaller segments. How and if the company will survive this transition is anyone’s guess, but the result is the same: fewer choices for consumers.

AMD

Over in the red corner, AMD is preparing its Radeon RX 7000 series graphics card for the limelight. Nvidia has given AMD a tremendous opening to compete in. The company is expected to showcase its new RX 7000 series graphics cards on Nov. 3. If they can deliver comparable performance, then AMD can easily price out its competitor. Still, there’s the possibility that AMD will follow suit and price its products equally high because, well, it’s a business and it wants to make money. Only time will tell. And yeah I guess Intel is here too.

Conclusion

The precarious amalgamation of events leaves many questions unanswered. How will Nvidia price the rest of its product stack? Will it introduce Super/Ti versions for both RTX 4080 variants? Will system integrators clearly specify the versions on their labels?

There are also intense debates around the products’ actual performance. While Nvidia claims a two to four times increase over the previous generation, many of the performance metrics shown during the presentation are in titles with both DLSS and ray tracing enabled. The company was a bit cagey about the new cards’ rasterization performance. A point to remember is that Nvidia can always adjust the MSRP later if the card doesn’t sell well.

The conversation will only heat up as we wait for the rest of the RTX 4000 lineup and the imminent details on AMD’s new products.